Big Cat Safety Incidents 2000 - 2018

Any time a dangerous wild animal is kept in a captive setting, there is an associated safety risk. Studying historical statistics and trends related to keeping big cats in human care can inform future risk management decisions.

Big Cat Safety Issues in the United States: 2000 - 2018

12/15/2018 - Rachel Garner

Any time a dangerous wild animal is kept in a captive setting, there is an associated safety risk. Big cats are one of the most commonly maintained dangerous wild animals in the United States, with sizable populations existing in multiple industry sectors as well as in private hands (Pfaff & Colahan, 2017; Chambers, 2017). It is difficult to track the relative safety risk these big cat populations pose as no single entity has the responsibility for tracking or documenting incidents. While a number of organizations track incidents that are relevant to their own interests, no comprehensive and publicly available data set of incidents involving big cat is known to exist in the United States. This study represents the first time multiple data sets comprising big cat safety incidents have been combined, with the goal of providing a starting point from which the statistics and trends involved in captive big cat risk management can be further assessed.

Data Acquisition

There is no entity in the United States tracking safety incidents involving captive wildlife, which makes identifying all possible candidates for a big cat safety incident list difficult. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) only records incidents that are reported (or observed) at facilities they license. Individual zoos and sanctuaries, as well as their accrediting organizations, likely record all incidents involving dangerous animals that occur at their specific facilities, but these records are not made available to the public if they do indeed exist. Incidents that occur in private settings can only be tracked when they are reported in the news or posted on social media. Given that there is no single source tracking the occurrence of incidents external to federal and state licensure, it is highly unlikely that there are more accurate data sets in existence than those maintained by the animal rights organizations that have been working for over a decade to end the private ownership of dangerous exotic animals.

Since each group compiling information has slightly different priorities for what sorts of incidents they track, and typically maintains their information in long form rather than in a searchable database, the best way to get as complete a picture as possible of what incidents it was possible to track was to combine all of the extant databases. While it is probable that not every incident in the country was recorded, the information that can be obtained from what is on record is extremely valuable. These extant records have already provided substantial enough information on big cat safety issues in the United States to influence legislators around the country and inform the creation of both state and federal laws (Manning, 2012; Humane Society of the United States; 2017).

Data Selection

The data set for this study was derived from records maintained publicly by four major organizations that track big cat safety issues: Born Free (Exotic Incidents Database; 2018), People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (Big-Cat Incidents in the United States, n.d.), The Humane Society of the United States (Big Cat Incidents, n.d.), and Big Cat Rescue (Baskin, 2018a; 2018b; 2018c; 2018d). Each source was included because the organization compiling it has a vested interest in maintaining an accurate and up-to-date record of incidents involving captive big cats in the United States, as well as the funding and staffing to facilitate such an effort long-term.

The following criteria were used to select data points included in the study:

Listed in at least one of the four sets of records

Occurred in the United States between 2000 - 2018

Involved a member of one of the “big cat” species defined by the Captive Wild Safety Act as well as any hybrid of those listed species

Presented an actual safety risk at the time of the recorded incident

Entries in the compiled data set were compared to eliminate redundancy and duplicate records. While all four of the sets of records used for this study contained incidents going back into the 1990s, only data from 2000 or later were used for this study because older incidents were much harder to verify independently. The resulting data set contained 359 distinct incidents that occurred over 18 years.

Incidents in the compiled data set were categorized by the species involved, the setting in which the incident occurred, the type of occurrence, and the outcome of the incident. Each category is described below.

Species

The Captive Wildlife Safety Act of 2003 defines “big cats” as including these species: tiger, lion, cougar, leopard, jaguar, snow leopard, clouded leopard, and cheetah. While hybrids of these species are not included in the regulatory definition, individual hybrid big cats are still safety risks and as such incidents involving them were included in the compilation.

Settings

Since the way a big cat was being kept or used was likely to be directly related to the risk of an incident occurring, incidents were categorized by the setting in which the incident occurred rather than the situation in which the animal was normally held. For instance, an incident with an animal owned by a zoological facility but taken to a mall for a cub-interaction venture would have been categorized by setting as “entertainment / outreach” rather than “zoological facility.”

Setting categories were defined as follows:

Attraction: An entity that exists for entertainment and tourism purposes but has an animal exhibition component.

Closed Compound: A situations in which an entity maintains a professional or semi-professional location for housing animals that is not open to the public.

Entertainment/Outreach: A business that facilitates animal-based entertainment, education, or outreach programs held away from where the animals reside (e.g., birthday parties with animal presentations)

Production Work: A company that uses their animal collection in the pursuit of artistic projects (e.g., movies, theater, photography).

Private Non-Professional: A situation where there is no business objective for having the animals.

Retail Services: A business where animal exhibition is a supporting factor of primary business objectives (e.g., steak house, pet supply store, bed-and-breakfast)

Sanctuary: A nonprofit business that provides a stationary collection of rescue animals with a permanent home. It may maintain an exhibition license either to allow the public to visit the site or for commercial support of the business.

Zoological Facility: A business that maintains a stationary collection of exotic animals for the primary purpose of public exhibition. It may be USDA-licensed, but is always open to the public for at least a period of time each calendar year.

Types of incidents

Attack: An incident in which a big cat made physical contact with a human in a manner inappropriate for the situation in which it occurred

Barrier Crossing: An incident in which someone specifically crossed, leaned over, or reached through a barrier that they were specifically prohibited from moving beyond

Escape: An incident in which an animal was outside it’s normal containment for a given situation

Dumped: An incident in which an animal was purposefully released in a public space

Public Endangerment: An incident in which someone removed a big cat from its proper containment, but remained in control of the cat

Outcomes

Death

Injury

No Injury

Results

The data will be reviewed several ways to elucidate trends. Results will be summarized by each category, by year, by the type of facility, and by outcome.

Breakdown by setting

Over the 18 year period evaluated, the majority of big cat safety incidents occurred in only two settings [Figure 1]: zoological facilities (39.3%) and private non-professional settings (36.0%). No other setting had anywhere near as high an incident rate, with the next highest, entertainment / outreach, producing only 9.1% of the total incidents.

Figure 1. Big Cat Safety Incidents by Setting

Breakdown by type of incident

The types of incidents that occurred over this 18 year period [Figure 2] were essentially equally divided between attacks (45.7%) and escapes (46.2%). A much smaller number of incidents occurred in this time frame when people crossed or reached across explicitly prohibited barriers (6.7%). Situations in which big cats were dumped, either dead or alive, or were involved in purposeful public endangerment comprise the remaining incidents.

Figure 2. Big Cat Safety Incidents by Type of Incident - All Situations

Breakdown by outcome

About the same number of incidents resulted in injuries (47.1%) over this 18 year period as did not result in injury (48.7%) [Figure 3]. Only a few incidents (4.2%) resulted in death.

Figure 3. Frequency of Injury and Death during Big Cat Safety Incidents - All Settings

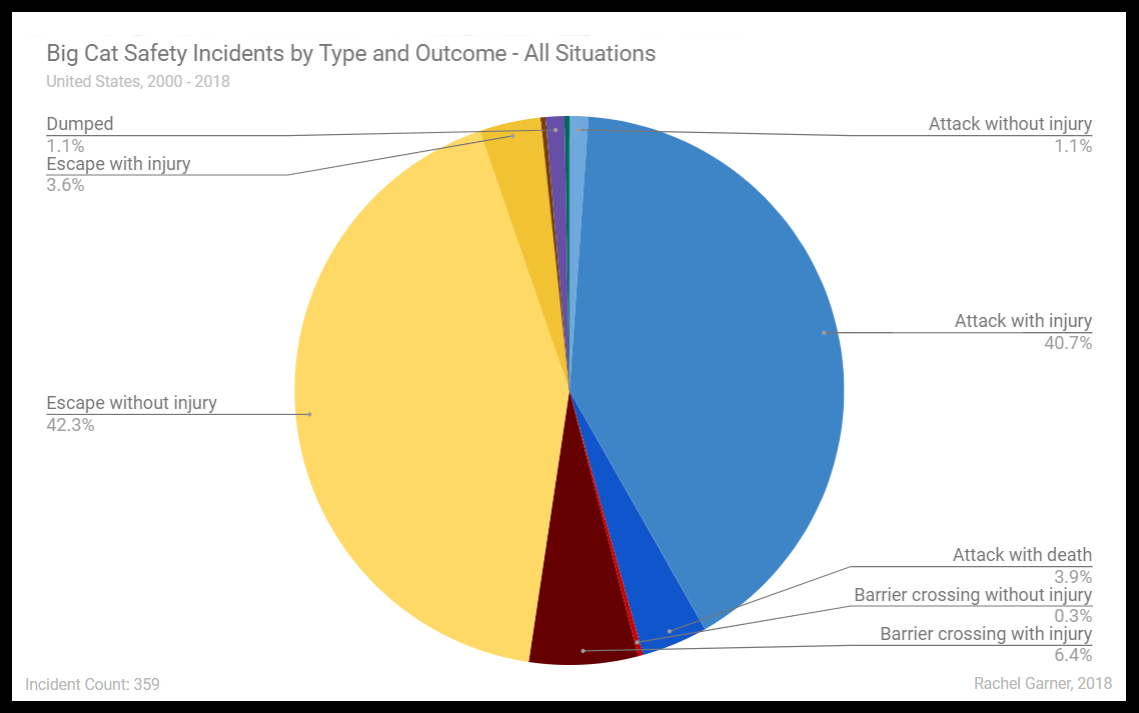

Summary by type of incident and outcome

When the data were broken down by both incident type and outcome, two patterns emerged as most common [Figure 4]:

Attacks in which one or more persons were injured

Escapes in which no human was injured

(While some of the escapes did result injury to another animal or damage to an inanimate object, tracking those results was outside the scope of this project.)

Figure 4. Big Cat Safety Incidents by Type and Outcome - All Situations*

*Unlabeled dark brown slice represents Escape with Death, 0.3%

*Unlabeled dark blue slice represents Public Endangerment, 0.3%

Breakdown by species

Incidents with tigers were by far the most frequent, comprising just under half (47.6%) [Figure 5]. Incidents with cougars were the second most frequent (21.6%), and incidents with lions were next (13.7%). None of the other species were involved in more than 7% of the incidents.

Figure 5. Species Involved in Big Cat Safety Incidents - All Settings*

*Unlabeled thin pink slice represents Ligers, 0.3%

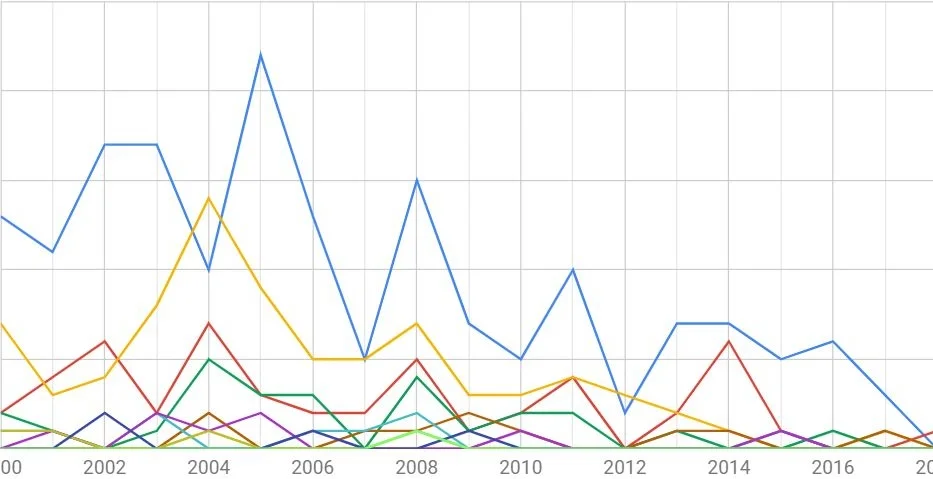

Total incident breakdown by year

Incident frequency was charted by total per year [Figure 6] to get a sense of the trends over time, and for the two settings in which the majority of incidents occurred (zoological facilities and private non-professional settings).

The largest number of incidents occurred in the early 2000s, from 2002 to 2005, although a spike was also observed in 2008. After 2008, the total number of incidents dropped sharply across the board, with only one big cat safety issue recorded in 2018.

Figure 6. Big Cat Safety Incidents by Year - Total from All Settings

Incidents in zoological facilities occurred with fairly consistent frequency up to about 2014 [Figure 7]. Zoological facilities had at least 5 big cat safety incidents per year in 15 of the 18 years covered, and 10 incidents or more in 6 of the 18 years covered. The number of incidents in zoological facilities decreased rapidly in the last few years off the period evaluated, dropping from 13 incidents in 2014 to five in 2015, and continuing to drop each year thereafter. This is consistent with the previous graph showing a decrease in the total number of incidents after 2014.

Incidents in private non-professional settings generally occurred more frequently than in zoological facilities during the early years of the period reviewed [Figure 8]. In addition, the frequency of incidents increased during the early years of the period covered, hitting the highest number of incidents per year in 2004. After 2005, the rate of incidents in this setting dropped sharply and stayed below 5 incidents per year from 2006 to 2018, with the exception of a single spike in 2008.

Figure 7. Big Cat Safety Incidents by Year -

Zoological Facilities

Click Image to View Full Size

Figure 8. Big Cat Safety Incidents by Year -

Private Non-Professional

Click Image to View Full Size

When frequency data by year for both zoological facilities and private non-professional settings were compared to the total number of incidents per year [Figure 9], it was clear that incidents in private non-professional settings were usually a large fraction of the total in the early 2000s, but that after 2008 incidents in zoological facilities comprised the majority of big cat safety incidents.

Figure 9. Comparison of Big Cat Safety Incidents Over Time by Setting

Yearly breakdown by species

Tigers were the most common species involved in big cat safety incidents each year [Figure 10], followed by cougars and then lions in a pattern that reflects the frequency with which those species were involved in the total number of incidents.

Figure 10. Species Involved in Big Cat Safety Incidents by Year

Breakdown by Zoological Facility

Attacks were the most common type of big cat safety incident at zoological facilities [Figure 11], with over half (50.4%) of the total incidents in 18 years. Escape situations were second most frequent, at 34.8%. The majority of the rest of the incidents in zoological facilities were caused by barrier crossings.

Figure 11. Big Cat Safety Incidents by Type - Zoological Facilities

Two-thirds of all incidents in zoological facilities ended in the injury or death of a person [Figure 12]. The majority of these (62.7% of total incidents) resulted in only injury, while 4.2% of the incidents led to someone’s death. The remaining one-third of incidents in the same setting were resolved with no human injury.

Figure 12. Outcomes of Big Cat Safety Incidents - Zoological Facilities.

Zookeepers, i.e. the people who worked directly with big cats, were the group most commonly injured or killed during the study period (41.8%), mostly as a result of attacks [Figure 13]. Adult members of the public were the next most common (38.8%); they were hurt both in attacks and in the majority of the instances of barrier crossing. Other zoo employees, volunteers, and young people were injured only about 20% of the time.

Figure 13. Groups Injured in Big Cat Safety Incidents - Zoological Facilities

Half of big cat safety incidents in zoological facilities involved tigers [Figure 14], with lions and cougars just about tying for second ranking at 12.4% and 11.7% respectively. Leopards were involved in almost as many incidents as cougars and lions, comprising 9.7% of the total incidents.

Figure 14. Species Involved in Big Cat Safety Incidents - Zoological Facilities

Breakdown by Private Non-Professional

More than two thirds of all big cat safety incidents in private non-professional settings during the study period were animal escapes [Figure 15]. Attacks were the next most common, at 26.9%, but occurred at less than half the frequency of escapes. A very small number of animals (3.1%) were found to have been dumped out of private non-professional situations.

Figure 15. Big Cat Safety Incidents by Type - Private Non-Professional

More than two-thirds of incidents occurring in private non-professional settings (72.3%), caused no injuries to humans [Figure 16], regardless of whether they were the result of attacks or escapes. Incidents causing injuries comprised only 25.4% of the total in private non-professional settings. People were killed in only 2.3% of the total incidents in private non-professional settings.

Figure 16. Outcomes of Big Cat Safety Incidents - Private Non-Professional Settings

Adults and children not responsible for animal care were the groups most frequently injured in private non-professional settings [Figure 17], at 40% and 34.3% of the total incidents respectively. The actual owners of the big cats were the next most likely group to get injured at 17.1%. Volunteers participating in animal care and teenagers not responsible for animal care were infrequent targets of big cats during the period studied.

Figure 17. Groups Injured in Big Cat Safety Incidents - Private Non-Professional Settings

Cougars were the most common big cat species involved in safety incidents in private non-professional settings (38.8%), with tigers a close second at 34.9% [Figure 18]. Lions were third most common, at 14.7%. No other species of cat was responsible for more than 6% of the total incidents during the study period.

Figure 18. Species Involved in Big Cat Safety Incidents - Private Non-Professional Settings

Breakdown by Injury and Death

While the number of people killed in big cat safety incidents in all settings over the 18-year period of the study was small, only 15, the majority of them spent a lot of time in proximity to big cats, or took care of them directly [Figure 19]. Deaths of animal owners and zookeepers comprised fully two thirds (66.7%), or 10, of those 15 deaths. Most commonly killed after that were guests who were visiting the cats (26.7%) where they lived, whether that was in an established facility or a private setting. During the study period, one volunteer who worked with or near the big cats was killed (6.7%).

Figure 19. Groups Killed in Big Cat Safety Incidents - All Settings

32 minors were injured or killed in big cat safety incident during the period of this study [Figure 20]. Children under the age of 13 were most likely to be injured (71.9%). Teenagers were injured at a much lower rate (15.6%) than children. But when minors were killed by big cats, an equal number of teenagers and children died (6.3% each).

Figure 20. Minors Injured or Killed by Big Cats - All Settings

Injuries to minors in big cat safety incidents occurred most frequently in private non-professional settings [Figure 21], at 40% for children and 6.7% for teenagers. But children under the age of 13 were also likely to get injured while visiting a zoological facility (16.7%) or interacting with big cats at an entertainment / outreach setting (13.3%). Teenagers were injured at a rate of just over 3% at each of zoological facilities, entertainment / outreach settings, and sanctuaries (3.3%)

Figure 21. Injuries to Minors During Big Cat Safety Incidents by Setting

Discussion

Data Sourcing

The data set compiled in this study cannot be 100% accurate for several reasons. Some recent incidents are missing from the databases used as source material, such as the July 2018 escape of a jaguar from his exhibit at the Audubon Zoo in New Orleans (Crespo, 2018), and it is likely that some older incidents may also be missing. Many of the records of big cat safety incidents in the source materials appear to have been obtained from media pieces covering the incidents rather than from direct reports. Occurrences that were not heavily publicized (or that were kept secret) are therefore likely not included. In addition, changes in technology as the world became more digitized over the study period mean that some information on older incidents may no longer be accessible or even kept on record, and there is no easy way to identify what, if any, potential data points have been lost. Despite the fact that the data set is not fully complete, however, it is probably the best data set that will ever be available for this time period, as the source material was specifically chosen from the extant public data sets likely to be the most comprehensive. Any missing data are likely to be but a small fraction of the total, however, since animal safety issues are generally considered highly newsworthy and inherently attract public attention. Even with some incidents missing, this compiled data set still provides vital information about where and how big cat safety incidents have occurred over time in the United States.

Misidentified wildlife

A thorough examination of the data set suggests that some wildlife sightings over the last two decades have been mistaken for sightings of escaped exotic pets, and have therefore artificially inflated the number of recorded big cat safety incidents. Over two dozen incidents were recorded, often in multiple databases, of large cats that were assumed by authorities to be escaped pets due to a belief that there were no large felids currently native to the area. Most of these were thought to be cougars, or were recorded in the source incident lists as “unidentified large felids.” Studies have shown that cougars, whose current range is generally reported as only being west of the Rocky Mountains, have been recolonizing the Midwest since the 1990s (Larue et al., 2012). Cougars are now thought to have established breeding populations in both North and South Dakota (Mountain Lion, 2016; Mountain Lion 2018), and evidence of at least transient wild individuals has been confirmed in multiple midwestern states (Michigan Radio Newsroom, 2012). Most of these “loose cats” included in the source material were sighted only a single time in rural areas in those same Midwestern states, and no potential owner for an escaped big cat was ever identified in the area. One specific animal that was counted by multiple groups as an escaped pet, hit by a car crossing a highway in Connecticut, was positively identified in 2012 through a genetics sample as a known male that had dispersed from a population in North Dakota and that was recorded on camera traps travelling through Minnesota, Wisconsin, and New York before his journey ended in New England (Larue et al., 2012). It seems probable that many cougar sightings that were deemed “escaped pets” were, in fact, just wildlife. Twenty-five animals identified in incidents in the data set as pets were judged more likely to have been wildlife, and set of corrected of graphs incorporating the elimination of those “escapes” were created and are shown below.

Figure 22. Big Cat Safety Incidents by Type and Outcome (Wildlife Differentiated)

Click Image to See Full Size

Figure 23. Big Cat Safety Incidents by Type - All Situations (Wildlife Removed)

Click Image to See Full Size

Figure 24. Outcomes of Incidents in Private Non-Professional (Wildlife Removed)

Click Image to See Full Size

Figure 25. Species involved in Big Cat Safety Incidents - All Situations (Wildlife Removed)

Click Image to See Full Size

Figure 26. Species involved in Big Cat Safety Incidents - Private Non-Professional (Wildlife Removed)

Click Image to See Full Size

Trends

There are some clear trends that can be identified from this initial examination of the incidents that occurred from 2000 - 2018, although additional historical context that was beyond the scope of this study would be required to interpret it more thoroughly,

While big cat safety issues occurred with some regularity in zoological settings and only dropped to consistently low numbers in the last few years of the study period, incident rates in private non-professional settings dropped drastically after 2008 and have been maintained at nearly zero. This trend may be due to regulatory changes affecting private big cat ownership during the study period and/or increased availability of husbandry and safety information online in private non-professional settings. Improved safety protocols and stricter licensing requirements from the USDA may have affected the operations of zoological facilities.

The frequency of species involved in incidents reflects the proportions of the known captive populations of big cats in the United States (Chambers, 2017; Culver, 2011). Tigers are the most commonly held large felid in zoological facilities (Tiger Species Survival Plan, 2018; Chambers, 2017) as well as in the private sector (Chambers, 2017), and were involved in the largest number of incidents during the study period. Lions and cougars were ranked second and third for both population statistics and recorded incidents. Even with the exclusion of the cougars considered to potentially be wildlife, cougars still caused slightly more incidents than lions in private non-professional settings. This is likely explained by the fact that the danger presented by cougars is easy to underestimate, due to their small size; without the strict safety protocols implemented in a professional management setting, cougars are perhaps less likely to be consistently treated as dangerous animals the way lions and other larger felids are.

Conclusion

As discussed previously, some conclusions can be drawn from an initial examination of this compiled data. Specifically, it is possible to identify the way misidentified wild felids may be influencing the data set, and to begin to get a sense of how the types of safety incidents that occur involving big cats have changed over the last two decades. Future research into the historical context surrounding big cat management in the United States during the study period can be utilized to identify addition trends in the data. Given the increasing public interest in big cat safety topics and the need for legislators and wildlife officials to understand where safety risks with captive big cats are highest, effective use of this database can serve as a tool for informing future advocacy and legislative efforts.

References

Baskin, C. (2018a, January 23). Big Cat Attacks 2006 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2018, from https://bigcatrescue.org/big-cat-attacks-2006-2010/

Baskin, C. (2018b, May 03). Big Cat Attacks 2011-2017. Retrieved December 14, 2018, from https://bigcatrescue.org/big-cat-attacks-2011-2017/

Baskin, C. (2018c, November 30). Big Cat Killings, Big Cat Maulings, Big Cat Escapes. Retrieved December 14, 2018, from https://bigcatrescue.org/big-cat-attacks

Baskin, C. (2018d, December 13). Big Cat Attacks 2000-2005. Retrieved December 14, 2018, from https://bigcatrescue.org/big-cat-attacks-2000-2005/

Big Cat Incidents (Publication). (n.d.). Retrieved December 14, 2018, from The Humane Society of the United States website: https://www.humanesociety.org/sites/default/files/docs/captive-big-cat-incidents.pdf

Big-Cat Incidents in the United States (Publication). (n.d.). Retrieved December 14, 2018, from People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals website: https://www.mediapeta.com/peta/pdf/Big-Cat-Incident-List-US-only.pdf

Chambers, K. (2017). 2016 Wild Feline Census. Retrieved December 14, 2018, from https://www.felineconservation.org/uploads/bltx_big_cats_by_species_and_type_of_facility_2016.pdf.

Crespo, G. (2018, July 16). Jaguar that escaped zoo enclosure may have bitten through steel barrier, officials believe. CNN. Retrieved December 14, 2018, from https://www-m.cnn.com/2018/07/14/us/audubon-zoo-jaguar-escapes/index.html

Culver, L. (2011). How many cats are in USDA licensed facilities in the US? (pp. 1-6). Feline Conservation Federation.

DNR confirms three recent cougar sightings in Upper Peninsula [Television broadcast]. (2012, November 28). Michigan Radio Newsroom. Retrieved December 14, 2018, from http://www.michiganradio.org/post/dnr-confirms-three-recent-cougar-sightings-upper-peninsula

Exotic Incidents Database (pp. 1-53, Publication). (2018). Born Free USA. Retrieved December 14, 2018, from https://www.bornfreeusa.org/?post_type=exotic_incidents&especies=LC&s=.

Sorted by "Big Cats"

Humane Society of the United States. (2017, March 31). Animal welfare coalition applauds reintroduction of “Big Cat Public Safety Act” to prohibit private ownership of dangerous big cats [Press release]. Retrieved December 14, 2018, from https://www.humanesociety.org/news/animal-welfare-coalition-applauds-reintroduction-big-cat-public-safety-act-prohibit-private

Larue, M., Nielsen, C., Dowling, M., Miller, K., Wilson, B., Shaw, H., & Anderson, C. (2012). Cougars are Recolonizing the Midwest: Analysis of Cougar Confirmations During 1990-2008. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 76(7), 1364-1369.

Manning, S. (2012, May 1). Ohio’s big cat stampede prods review of laws nationwide. Centralmaine.com. Retrieved December 14, 2018, from https://www.centralmaine.com/2012/05/01/ohio-wild-animal-stampede-ignites-vast-law-review/

Mountain Lion. (2016). Retrieved December 14, 2018, from https://gf.nd.gov/wildlife/id/carnivores/mountain-lion

Mountain Lion. (2018). Retrieved December 14, 2018, from https://gfp.sd.gov/mountain-lion/

Pfaff, S., & Colahan, H. (2017, June 16). African Lion Regional Studbook. Retrieved December 14, 2018, from Association of Zoos and Aquariums.

Tiger Species Survival Plan. (2018). Retrieved December 14, 2018, from http://support.mnzoo.org/tigercampaign/tiger-ssp/