How To Understand Zoo Animal Training

A good training program is vital to helping zoos take care of their charges. While most people think of ‘exotic animal training’ as the whips and chains immortalized in old images, modern zoos have chosen voluntary, reward-based training methods that make training sessions some of the most enriching parts of an animal’s day.

How To Understand Zoo Animal Training

8/27/2018 - Rachel Garner

A good training program is vital to helping zoos take care of their charges. The animals in zoo collections aren’t being trained for obedience, like we train domesticated pets; instead, they’re learning how to cooperate with their keepers as part of their daily routine, how to showcase natural behaviors on cue for educational programs, and even how to participate voluntarily in their own veterinary care. While most people think of ‘exotic animal training’ as the whips and chains immortalized in old images, modern zoos have chosen voluntary, reward-based training methods that make training sessions some of the most enriching parts of an animal’s day.

How The Science of Training Works:

The type of training zoos use almost exclusively is called positive reinforcement training. Positive reinforcement means that the trainer is adding something to the interaction to make a behavior more likely to happen again. So when an animal does something that the trainer is looking for, they let the animal know with a marker noise (generally by saying “yes” or“good”, or by using a whistle or clicker) and then reward them by giving them something the animal really likes.

While this type of training sounds pretty intuitive and like something you might have done with your own domestic pets, it's actually very heavily rooted in the science of how animals learn. Since all animals learn the same way, anyone with a fundamental understanding of learning theory can apply the same techniques to train any organism.

If you’ve ever taken a psychology class, you'll probably recognize the terms 'classical conditioning' and 'operant conditioning'. These two theories underlay every way that we're able to produce behavioral change in an animal. Classical conditioning comes from the iconic experiment where Pavlov rang a bell before feeding his dog and eventually the dog started to drool - pairing a stimulus with an outcome repeatedly meant that the new stimulus (the bell) eventually elicited the same physiological response (drooling) as the original stimulus (the food).

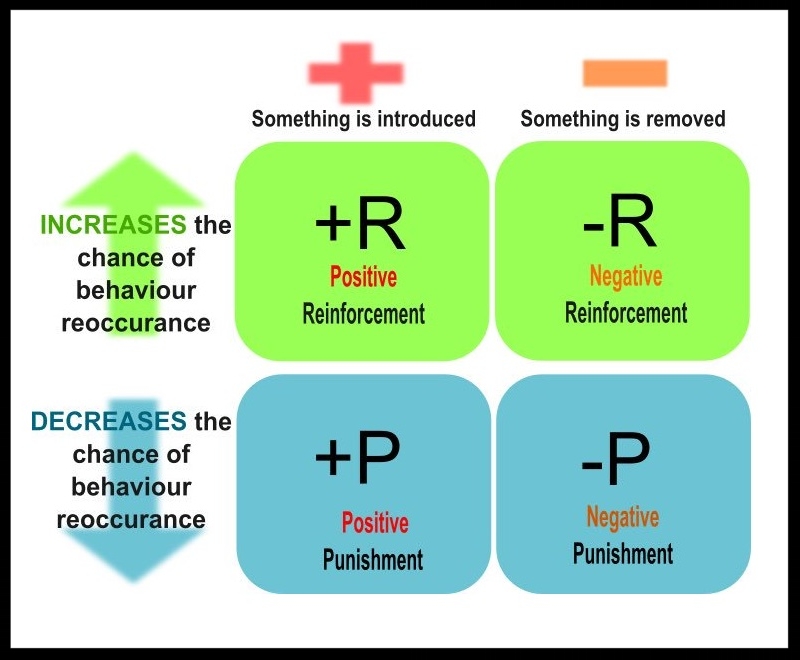

Positive reinforcement is one of the “four quadrants" of operant conditioning. Operant conditioning as a theory is not training-specific - it actually defines how animals will be likely to behave due to the consequences of their previous actions. Any interaction an animal could possibly have with anything in their environment will, by definition, fall into one of the four possible quadrants. While not designed specifically for animal training, operant conditioning theory allows animal training to be highly successful; with a thorough understanding of what makes animals adjust their behavior and how they change what they do, a good trainer can set up a session to help their animal learn successfully and quickly. Some of the terminology used when talking about animal training is very jargon-heavy, let's take a moment to define the terminology of operant conditioning before moving on to how it's applied.

Photo Credit: AP Psychology Twitter

For the purposes of talking about operant conditioning and learning theory, ‘positive’ simply means ‘to add’ and ‘negative’ means ‘to take away’. 'Reinforcement' means that something makes a behavior more likely to happen, and 'punishment' means something that makes a behavior less likely to occur again. So when we’re looking at the four ways you can influence an animal’s behavior, we’ve got:

Positive Reinforcement (R+): adding a stimulus to make a behavior more likely to happen again

Negative Reinforcement (R-): removing a stimulus to make a behavior more likely to happen again

Positive Punishment (P+): adding a stimulus to make a behavior less likely to happen again

Negative Punishment (P-): removing a stimulus to make a behavior less likely to happen again

Why Primarily Positive Reinforcement?

Of the four quadrants, positive reinforcement is the best method for creating behavioral change in an animal. While all quadrants will modify an animal's behavior when utilized correctly, some are frequently unpleasant (like positive punishment), and positive reinforcement is the only quadrant through which you are specifically communicating to the animal you're training what it needs to do to be successful and rewarding it for making that choice. There's no confusion generated by being told what not to do without being given any information about what to do instead, and no brute physical manipulation or stressful handling by the trainer to achieve the behaviors they want. If the animal becomes frustrated or confused, the trainer just goes back to something the animal knows well until the animal is successfully engaged again, and then goes back to the last step of what they were working on before that the animal is confident with. That type of interaction builds a strong relationship between the animal and its trainer(s), because the entire experience is designed intentionally to be positive for the animal.

Anything an animal values can be a reinforcer, which leaves lots of room for trainers to be creative and consistently change up what they're rewarding animals with - which makes the whole experience more engaging and exciting for the participants. Some animals will do anything for a favorite snack, but for others a primary reward might be a scratch behind the ears or a chance to play with a favorite toy. Zoo animals are never deprived of anything to encourage them to work for it - instead, reinforcers function like extra special bonuses during the day.

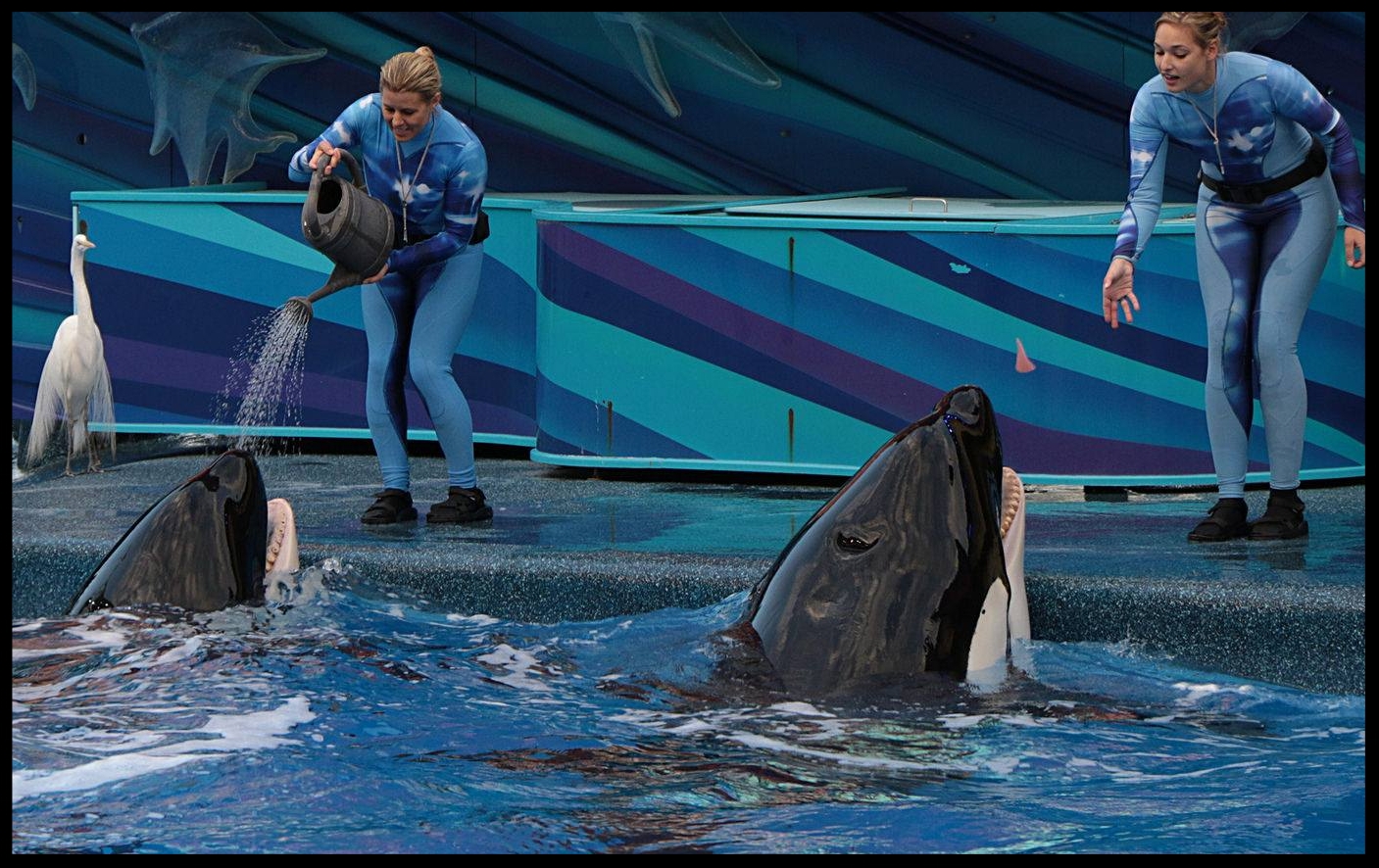

Orcas at SeaWorld Orlando receiving different types of reinforcement: the whale on the left is getting a tactile reinforcer in the form of a pouring watering can, whereas the whale on the right is being tossed a chunk of jello as an edible reinforcer.

Photo Credit: M. Hummel-Uzzi

A cheetah at Busch Gardens drinks hot chicken broth - his favorite reinforcer - from a squirt bottle during a public demonstaration.

The most imporant aspect of using primarily positive reinforcement training is that animals are always engaging voluntarily. Zoo animal training sessions are always set up so that the animal chooses if it wants to come over for the session, and it only stays as long as it feels like engaging. When the animal walks away, the training session is done. Most of the time, animals come over immediately because they like training: there's a lot of research that shows animals will choose to work because it's interesting and engaging even when they have everything they already need, and it's the same for training sessions. Zoo animals are motivated to engage in training by their relationship with their trainer, and the fact that they're doing novel and complicated work while receiving a paycheck in whatever reinforcer counts as "currency" for that specific individual. Does this mean that there are some days animals would rather do other things and just don't engage? Absolutely. And while it may be a little frustrating for the animal keepers to not be able to train that day, that's just how it goes - they feed and care for the animal like normal, wait until the animal decides they want to come over for a training session, and then use unique and special reinforcers to make it super awesome and worth the animal's time.

What Kinds of Zoo Animals Can Be Trained?

The great thing about using operant conditioning techniques for training is that they are able to be generalized to literally any species of animal. The quadrants indicate what kind of stimulus needs to be added or removed to a situation to change behavior - it's up to the trainer to figure out what will be successful with each species they want to work with. In order to do so, the trainer needs to understand a lot about the natural history of the species they're looking to train, as well as the specific personality and preferences of the individual animal they'd be working with.

Some animals, like snakes, eat really infrequently, so a training plan for them has to take into account that food-based reinforcers can only be used at most once every couple of days. Either this means that the trainer finds an alternate reinforcer the snake will work for (which doesn't always exist), or they just accept that training behaviors with that snake might take much longer than it would with a mammal. And that's fine - that's just how snake training goes, and zookeepers work with that rather than trying to force it to change.

Other animals might need a modified training session because their species (or specific individual life history) prevents them from being able to perceive the "marker" cue (called a bridge) that trainers use to tell them when they've completed a behavior correctly. A flash of light is often used to bridge fully aquatic or deaf animals, and an old animal with reduced hearing and sight might have a tactile bridge.

The method of successful reinforcer delivery is also factored into how training situations work with different species. Primates can frequently just be handed food directly once they have a good relationship with their trainer, but large carnivores are generally fed meat treats from tongs or a long stick to make sure they don't accidentally take a a finger along with it. Cetacean trainers generally throw food directly into the open mouths of their animals, but a blind sea lion might require the food to be touched to her nose so she knows where it is in order to grab it. Fish are generally fed reinforcers directly from a stick, to ensure the correct animal in the tank actually gets the reinforcer that was meant for it, as well as to keep excess food from falling to the bottom and being wasted.

How Does A Normal Training Session Go?

The keepers who are training that day will collect all the things they need for the session: a variety of reinforcers, whistles or clickers to use as a bridge, tools or props needed for specific behaviors, and any required safety gear for being in close proximity with animals. They'll take the whole kit over to the space designed as a training area and get set up, and then call over the animal being trained. What happens during that session will depend on a lot of factors: the experience of the trainer, the relationship between the trainers and the animal, and what the current training priorities are, as well as potentially how the animal is feeling that day, the behavior of conspecifics, and what the weather is like.

A selection of things that might be brought to a training session with a cetacean: a bucket of fish, a soft tactile brush, a favorite toy, chunks of unflavored gelatin, and a whistle for use as a bridge cue.

Long before trainers start actually working on behaviors with an animal, they have to first establish a positive relationship with them. This starts just by spending time with the animal, being around at the fence line so the keeper becomes familiar, and then they might progress to feeding the animal or shadowing their existing trainers during sessions. Once the animal responds to the potential trainer's approach in ways that indicate positive excitement and interest, the person is finally able to start working on training.

A California sea lion at the Turtle Back Zoo waits as its trainer reaches for a piece of fish during a session.

Photo Credit: Turtle Back Zoo

An opossum at the Nashville zoo waits as she is handed a mealworm as a reinforcer.

Photo Credit: J. Belair

New trainers first start by being 'transferred' the behaviors an animal already knows how to do for other people. This ensures that the new trainer is aware of what the animal has already learned and that what they're doing is consistent with the work of the other trainers. If a new trainer's criteria for a successful behavior is suddenly different than what the animal has learned is expected of it, that can be really frustrating for the animal; this can lead to behavioral problems during training sessions or a lack of interest in engaging with training sessions at all. As a result, new behaviors are generally taught by one person or by a small collaborative team until they're solid, and then slowly all of the animal's other trainers are taught how to ask for and reward it correctly. All "training in" of new people is done at a pace that ensures that both staff and the animal are comfortable with each step before asking them to proceed to the next - this is especially true with any behaviors that involve any sort of contact between the trainer and their animal, or any work done without barriers between the two. Once any new team member is up to speed with all of the extant behaviors an animal knows, they might get to start working on something new.

A trainer at Tiger World demonstrates to a training class how to appropriately present a reinforcer to a large carnivore.

In order to work on a new behavior, trainers generally have to draft a formal training plan and submit it to their area lead (or the zoo's behavioral husbandry department, if they have one). This will detail the processes through which the behavior will be achieved and proofed, and what criteria will be used to determine when the animal is ready to move onto the next step. Sometimes these plans also list types and amounts of reinforcers to be used during the training, so that it can be double-checked that they're appropriate (for instance, to make sure calorie intake is appropriate or to make sure a food a specific animal can't eat isn't accidentally included). Once approved, the person working on the new behavior will keep records of their training sessions in which they detail everything that happened during the session. These go into the rest of the animal's records, so that other team members and management staff can stay appraised of anything that might be influencing an animal's behavior.

New behaviors are generally taught through a process called shaping, where the trainer starts by cuing a behavior the animal already knows how to do, and then slowly over time changes the criteria for getting a reinforcer to something just a little bit closer to the goal behavior. Over time, the desired behavior is "shaped" through these gradual approximations.

A keeper at the Twycross Zoo works on an approximation for a voluntary injection behavior with a chimpanzee. Once the animal is comfortable being sitting calmly while being poked in the shoulder with a finger, the keeper might progress to using a dowel, then a syringe without a needle, then a blunted needle, and finally a sharpened needle that actually gives the chimp a poke.

Photo Credit: K. Waller

What Are Zoo Animals Trained To Do?

A successful training program can touch every aspect of a zoo animal's life. A majority of the training zoo animals engage in is geared towards voluntary medical participation, but trained behaviors also teach animals how to be better mothers, help zookeepers complete their daily routine, allow animals to educate guests through a demonstration, assist in moving animals around the facility easily, and are sometimes just a fun and enriching activity for the animal to engage in.

Target Training

One of the first behaviors every zoo animal is taught is "target training." It's a very simple behavior: the animal is asked to touch a specific body part - frequently their nose - to an item that is designated as the "target". Target training is a very fundamental behavior in zoo training programs because it is a great building block for shaping most of the other behaviors an animal will learn in its lifetime.

A red panda at the Sacramento Zoo doing a "nose target" behavior.

Photo Credit: M. Owyang

An Amur leopard at the Franklin Park Zoo doing a "nose target" behavior through a training wall.

Photo Credit: Franklin Park Zoo

A Bactrian camel at the Franklin Park Zoo doing a "nose target" at his exhibit fence.

Photo Credit: Franklin Park Zoo

Targets can also be useful for when training at a distance, or in the water. A long target pole allows a trainer to cue an animal into a specific position without sharing space with them directly, or having to get too close. Cetaceans are frequently directed to a specific area of the pool to perform a behavior through a target pole being slapped on the water, and target objects hanging above the pool on a line are used to shape aerial behaviors.

A North American river otter at the Aquarium of the Bay doing a "wait" behavior while in position for a

nose target.

Photo Credit: D. Estes

A Commerson's dolphin at Aquatica follows a target pole while learning a "belly flop" behavior.

Photo Credit: M. Hummel-Uzzi

An orca at Six Flags Discovery Kingdom leaps to touch a suspended target with her rostrum.

Photo Credit: M. Owyang

Targeting is a particularly useful behavior to teach aquatic animals, because it allows them to be fed directly from a target pole - this allows aquarists to ensure all of the fish in a tank get something to eat, and lets them measure the amount of food each fish is getting.

A lionfish at the Cameron Park Zoo targets to a pole bearing a chunk of fish.

Photo Credit: D. Estes

A moray eel at the Cameron Park Zoo approaches a target pole.

Photo Credit: D. Estes

A stingray at the Cameron Park Zoo takes a piece of food off of a target pole.

Photo Credit: D. Estes

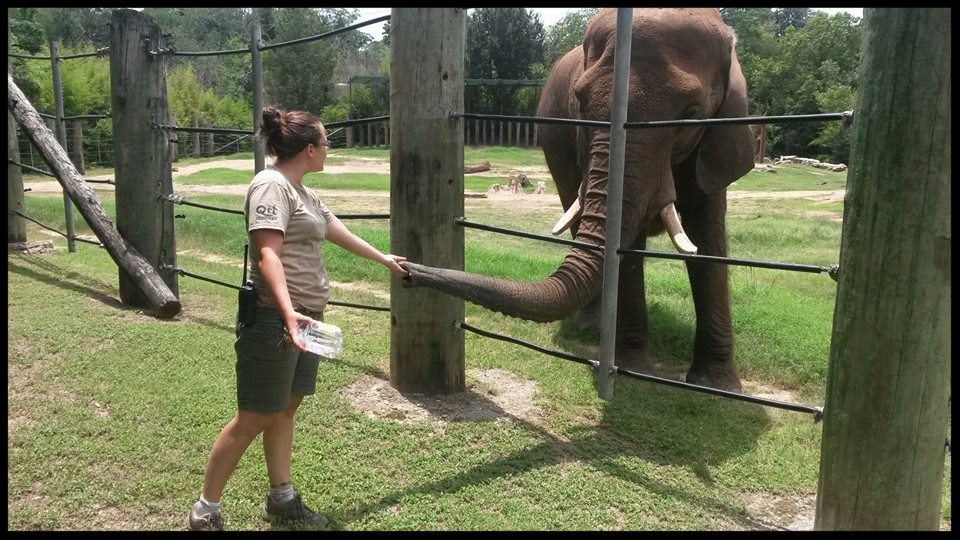

An African elephant at the Cameron Park Zoo doing a "trunk target" behavior to a zookeeper's hand.

Photo Credit: Cameron Park Zoo

A skink at the Franklin Park Zoo doing a "nose target" behavior while on a perch for a public demonastration.

Photo Credit: C. Rutledge

A six-banded armadillo doing a "nose target" at the Sacramento Zoo.

Photo Creidt: M. Owyang

A reticulated giraffe at the Turtle Back Zoo doing a "nose target" to a zookeeper's hand.

Photo Credit: Turtle Back Zoo

Station Training

Another crucial behavior that zoo animals learn early is called a "station." A station is simply a spot where an animal has been trained to go on cue and stay there. Stations can be a stump or a perch or even just a specific spot on the floor. Stations allow trainers to ask animals go to particular locations during a training session, and lets them manage a multiple animal session by asking each animal to sit patiently at its station until it is that animal's turn to work on a behavior.

An American Aligator holds at a "control station" while staff at Theater of the Sea work in his exhibit.

Photo Credit: K. Rivera

Open Mouth

Another really important and incredibly common behavior is the "open mouth" cue. It can be done with any species that has a mouth to open, and is used to allow staff to assess animals' oral health without an invasive procedure. The animal is first taught to open their mouth on cue, and then taught to hold it for a decent duration. If an animal's mouth or teeth need medication or frequent care, they'll be asked to stand still and allow touch and manipulation of their lips and jaws as part of the behavior.

An African lioness at the Houston Zoo doing an "open mouth" behavior.

Photo Credit: K. Buckley-Jones

A North American river otter at the Aquarium of the Bay doing an "open mouth" behavior while holding a "nose target" on a target pole.

Photo Credit: D. Estes

A Commerson's dolphin at Aquatica doing an open-mouth behavior.

Photo Credit: M. Hummel-Uzzi

An African Elephant at the Atlanta Zoo doing an "open mouth" behavior with her trunk up so keepers can see inside of her mouth easily.

Photo Credit: T. Phillips

Body Examinations

Preventative veterinary work requires that zookeepers and veterinary staff are able to get a close look at a zoo animal's body on a regular basis. Many animals in zoos are trained to present different body parts to their trainers for examination. Once animals know how to "target", trainers can use that skill to ask animals to present any part of their body to them or position it against a fence for close inspection. Zoo animals are commonly taught to present their feet to trainers, as well as their eyes, ears, stomach, flank, and tail.

A jaguar at the Houston Zoo doing a "body presentation" behavior at the exhibit fence, while being reinforced with milk from a squirt bottle.

Photo Credit: K. Buckley-Jones

A tiger at Great Cats World Park doing a "body presentation" behavior during a demonstration for guests.

Photo Credit: Great Cats World Park

An African Elephant at the Atlanta Zoo doing a "foot presentation" behavior while a staff member looks at the health of her feet and toenails.

Photo Credit: T. Phillips

Many examination behaviors also double as great presentation behaviors because they allow guests to get a unique up-close view of a wild animal's size, teeth, or claws. Once animals know how to "target", trainers can use that skill to ask animals to present any part of their body to them or position it against a fence for close inspection . Zoo animals are commonly taught to present their feet to trainers, as well as their eyes, ears, flank, and tail.

A tiger at Tanganyika Wildlife Park doing a "foot presentation" behavior during a public training demonstration.

Many of the interactive behaviors zoo guests will see during aquatic animal presentations, while cute, are actually behaviors the animals have learned for examination purposes.

An orca at SeaWorld Orlando doing a "flipper presentation" behavior during a show.

Photo Credit: M. Hummel-Uzzi

California Sea Lions at the Brookfield Zoo doing "flipper presentation" behaviors during a daily training session.

A blue and gold macaw doing a "wing presentation" behavior at the Chessington World of Adventures Resort.

Photo Credit: L. Partridge

During regular daily training sessions, zoo animals are asked to do multiple different body presentation behaviors so their keepers can assess their whole body for potential injuries.

A mandrill at Tanganyika Wildlife Park doing a "body presentation" behavior.

Photo Credit: A. Hawkins

The same mandrill doing a "hand presntation" behavior.

Photo Credit: A. Hawkins

The same mandrill doing an "open mouth" behavior.

Photo Credit: A. Hawkins

Medical Care

The benefit of having a really intensive and proactive medical training program is that when animals do get sick or injured and need treatment, they've already learned the skills that will help expedite their care. Zoos train animals for all sorts of medical procedures, such as blood draws, injections, and ultrasounds, just in case they might need that type of treatment someday.

A trainer at Dolphin Quest Bermuda uses a sustained "open mouth" behavior to examine a bottlenose dolphin's teeth carefully for wear or damage.

Photo Credit: M. Minikin

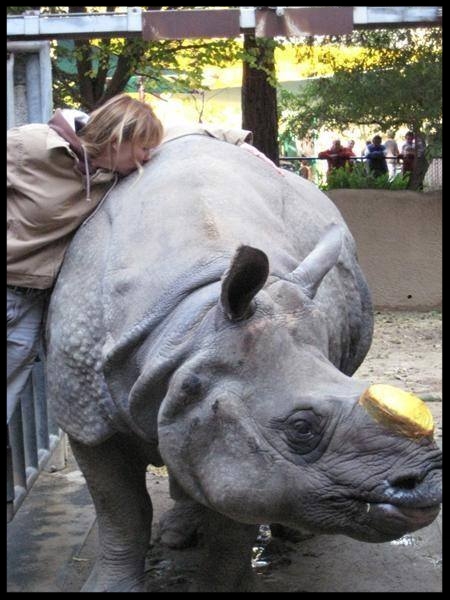

A greater one-horned rhinoceros at the Los Angeles Zoo was trained to allow the application of a special bandage when her horn became cancerous and had to be removed.

Photo Credit: J. Pham

A white-tailed deer at the Brevard Zoo licks at a fruit smoothie for the duration of a voluntary blood draw.

Photo Credit: R. Smith

A cougar at at America's Teaching Zoo holds still while blood is drawn from a vein in its tail.

Photo Credit: A. Howland

When animals need more diagnostics to complete their care, those behaviors are often also trained as well.

A trainer at SeaWorld Orlando palpates a bottlenose dolphin's bladder in preparation for collecting urine with the syringe held in his other hand. The dolphin has been trained to "station" on the trainer's outstretched legs and then urinate on cue.

A saki monkey working on a voluntary X-ray behavior at the Elmwood Park Zoo.

Photo Credit: K. Olsen

A siamang waits while a keeper takes a blood pressure reading from an arm cuff at the Brevard Zoo.

Photo Credit: K. Castrucci

An orangutan at the Cameron Park Zoo hangs out while keepers and vet staff gather data with a three-lead electrocardiogram.

Photo Credit: L. Klutts

A ring-tailed lemur allows a voluntary ultrasound of her abdomen at the Cameron Park Zoo.

Photo Credit: L. Klutts

Any animals with on-going health issues (such as arthritis or skin problems) will be trained to accept a daily dose of the appropriate medicine, or to allow staff to apply treatments topically.

A trainer at the Downtown Aquarium in Denver demonstrates how they apply medication to a North American river otter's hind feet through the use of a "nose target" and a "roll over" behavior.

A coatimundi at the Chessington World Park and Resort practices taking medicine from a syringe.

Photo Credit: L. Partridge

A Harris's hawk at the Texas State Aquarium holds a "beak target" behavior to one trainer's hand, as another prepares to put ointment on his eye. The hawk has been trained to put his head through a hole in the side of a carrying crate for this procedure.

Photo Credit: A. Henry

A keeper at the Twycross Zoo trains a mother orangutan to let her give her infant oral medication through cooperative feeding.

Photo Credit: K. Waller

An American Crocodile waits at a "station" on dry land at the Theater of the Sea while a topical treatment sinks into its foot.

Photo Credit: K. Rivera

Voluntary engagement in medical behaviors is an important part of all zoo animals' care, but a truly crucial aspect of successfully managing the largest zoo residents. Smaller animals can be physically restrained for medical care in an emergency situation, but an elephant is practically impossible to treat if it decides it doesn't want to cooperate.

An orca at SeaWorld Orlando "stations" on a scale so trainers can record her weight.

Photo Credit: M. Hummel-Uzzi

A black rhino at Zoo Atlanta stands patiently while a veterinarian ultrasounds her abodmen to check for a successful pregnancy.

An American Alligator at Theater of the Sea climbs onto a stationary scale.

Physical Therapy and Exercise

In addition to helping animals while they're sick, a good training program helps animals with the recovery process after an injury and also keeps them in strong and in shape.

A dromedary camel at a zoo in Kentucky stretching into a "nose target" behavior as part of physical therapy for his stiff neck.

The same dromedary camel allowing leg manipulation by his trainer as part of his PT.

The same dromedary camel following a "nose target" into a another deep stretch during PT for his stiff neck.

An Asian elephant at the National Zoo doing a "bow" behavior during a public demonstration. This behavior is a good stretch and helps keep elephants limber.

An African elephant at the Birmingham Zoo working on a "salute" behavior. This behavior requires both strength and balance, and is a complicated behavior to learn that provides the elephants with mental enrichment.

Photo Credit: B. Beury

Getting Around the Zoo

Zoo animals will frequently need to travel to other parts of the zoo - to a new exhibit, to the vet, to a public presentation, or even off-grounds - and it's easier for everyone if they're already trained for transport so that they stay calm and comfortable during the process.

The most common type of transport training is called "crate training" and it's as simple as it sounds - the animal is rewarded for voluntarily entering and spending time in a travel-sized carrier. The animals first get comfortable with the door being open, and then with it shut for progressively longer duration, and then finally with it being moved. Crate training helps to reduce stress during transport because the animal is getting to choose to enter a space it has a long history of positive experiences with.

Fulvous Whistling Ducks at the Sacramento Zoo entering their transport crate.

Photo Credit: M. Owyang

The same Fulvous Whistling Ducks calmly settled inside their transport crate en route to a presentation.

Photo Credit: M. Owyang

Crate training also provides a safe way for zoo staff to interact with potentially dangerous or aggressive animals. Stationary crates are often outfitted with doors that allow trainers to access specific parts of an animal's body without putting themselves too close to claws or beaks. One trainer will work with the animal, reinforcing them for staying in the crate and keeping calm, while another utilizes the access doors to examine or treat the necessary area. Crate training is also often the least-stressful way to sedate an animal that needs major medical treatment - they can be injected with a sedative while in an safe, enclosed space and then transported to the veterinary hospital in that same crate.

A double-wattled cassowary at the Birmingham Zoo waits inside his crate for his trainer to deliver a favorite reinforcer. This crate allows keeper staff to work with him at close range while keeping a solid barrier between them and his strong, heavily clawed feet at all times.

Photo Credit: Birmingham Zoo

Another option for moving animals is to simply train them to wear a harness and to walk next to their trainers on a leash. This is a training type used more frequently for ambassador animals that are specifically trained to take part in educational demonstrations and outreach programs. Harness training is a long, gradual process that involves getting the animal comfortable with putting on and wearing the harness, as well as teaching them how to follow a trainer from point A to point B, before they ever leave their enclosure.

A red panda at the Sacramento Zoo waits on a walk while wearing a harness on the way to a public program.

Photo Credit: M. Owyang

A harnessed aardvark at Omaha's Henry Doorley Zoo digs up the zoo grounds on a walk while her trainers do an informal education session with zoo guests.

A cheetah at Busch Gardens follows a "nose target" cue up onto a platform during a public demonstration.

While many zoo animals only wear harnesses for the purpose of taking part in specific programming, getting to go on self-directed walks simply to explore the zoo grounds is a form of environmental enrichment for others.

A red river hog at the Cincinnati Zoo stops to sniff the breeze while exploring the zoo grounds wearing his harness.

Photo Credit: K. Meeker

A serval at the Nashville zoo explores the facility grounds with a trainer on a snowy morning.

Photo Credit: C. Wheeler

A harness-trained emu is walked through the grounds of the Staten Island Zoo by its trainer.

Photo Credit: R. Ayers

Some zoo animals are taught to travel with or to fly to trainers entirely without wearing gear. This is mostly a practice maintained with flighted birds that take part in public demonstrations, but sometimes it's a technique used with other types of animals.

A juvenile black crowned crane at Natural Encounters learns to walk alongside its trainer without a harness or leash.

Photo Credit: M. Davies

A giant Indian fruit bat at Six Flags Discovery Kingdom practices flying from a perch to the arm of his trainer.

Photo Credit: K. Hyde

Acting On Cue for Education

Most zoo animals have an incredible range of unique and specialized behaviors that are a major part of their species' survival and success in the wild. One major use of training in zoos is putting those behaviors on cue so that guests can learn about species-specific adaptations by seeing them first-hand. These are the behaviors you'll see the most of in educational demonstrations and outreach programming, although often they'll be interspersed with medical behaviors or body presentations as well.

A coatimundi at the Chessington World of Adventures Resort demonstrates the species' agility and climbing ability by running across a rope upside-down.

Photo Credit: L. Partridge

An Amazon parrot at the Chessington World of Adventures Resort shows off its flying skills ..

Photo Credit: L. Partridge

A meerkat shows off the species' natural "sentry" behavior at the Chessington World of Adventures Resort.

Photo Credit: L. Partridge

A tamandua at Six Flags World Park demonstrates how strong a tail the species has by hanging from it.

Photo Credit: A. Hawkins

A blue and gold macaw hangs by its beak during an educational presentation at the Chessington World of Adventures Resort.

Photo Credit: L. Partridge

A California sea lion shows off strength and stamina by doing a "flipper stand" at the Chessington World of Adventures Resort.

Photo Credit: L. Partridge

The same California sea lion engages in a "stretch" behavior to show off the species' range of motion and flexibility at the Chessington World of Adventures Resort.

Photo Credit: L. Partridge

Demonstrating the incredible bird-hunting skills of its species, a serval jumps for a lure during programming at the Columbus Zoo.

Photo Credit: Katie Fox

Sometimes the natural or adaptive behaviors put on cue are not exactly what guests expect to see at a zoo, but are important things to show the public as part of specific types of messaging: it's common to see parrots screaming on cue to help explain why they don't make good pets, or urban wildlife demonstrating exactly how good they are at getting into unsecured trash.

A raccoon at the Chessington World of Adventures Resort demonstrates how easily it is able to get into a typical trash bin during an educational demonstration.

Photo Credit: L. Partridge

The same raccoon poses for photos in the trash can after the demonstration ended.

Photo Credit: L. Partridge

Sometimes, even "unnatural" behaviors can really get people to engage with specific types of messaging. It's currently very popular to have presentation animals demonstrate environmentally-conscious behaviors the zoo is encouraging guests to start doing, such as recycling.

A California sea lion at the Chessington World of Adventures Resort places a plastic bottle into a recycling bin during an educational presentation.

Photo Credit: L. Partridge

Silly Things

The process of training - learning new behaviors, figuring out ways to combine old behaviors, or practicing something that's physically challenging - is a really good type of environmental enrichment for all animals in human care. To keep their animals engaged and learning new, novel things all the time, zoos will often offer animals the chance to learn fun or silly behaviors. The animals aren't forced to learn any of them: if an animal isn't interested in training on a behavior that isn't crucial to their medical care or husbandry, trainers will let it drop, and find something else that the animals finds more engaging to learn or do instead. However, lots of animals eagerly engage with these behaviors and sometimes even prefer to do them over their other trained behaviors.

A bottlenose dolphin at SeaWorld Orlando sticks her tongue out in response to a "joke" cue from her trainer.

A California sea lion at the Chessington World of Adventures Resort hides its face in response to a "look guilty" cue during a presentation.

Photo Credit: L. Partridge

A blue and gold macaw at the Chessington World of Adventures Resort holds a clicker and shows guests that he knows how to bridge himself during his own training session.

Photo Credit: L. Partridge

Interaction

Guests visit a zoo because they love animals and want to learn about them and see them up close. Historically, zoos have allowed guests to interact with animals whether the animals wanted it or not; modern zoos, understanding how much it makes a visitor's day to actually get to interact with a zoo animal, have switched to allowing interactions with specifically trained animals - and only when the animals feel like it.

For most interaction behaviors, the animal is specifically taught to do a certain behavior with people other than its normal trainers (generally, a nose or paw target, but sometimes it's simply taking food from them). Visitors are brought to a specific interaction area and the animal is offered the choice of engaging with them in return for very high-value reinforcers. If the animal doesn't choose to come do the interaction that day, or appears to be uncomfortable, the trainers running the session allow the animal to make that choice and explain to the guests why voluntary engagement is such a crucial part of succesful animal training.

A North American river otter doing a "nose target" behavior to a target pole held by guests during a special behind-the-scenes interaction prgoram.

A grey fox at the Sacramento Zoo "high-fives" his trainer on cue.

Photo Credit: M. Owyang

A North American River Otter at the Aquarium of the Bay holds a "nose target" behavior while presenting his paw for a tactile behavior.

Photo Credit: Aquarium of the Bay

An American Alligator "painting" on a canvas during an interaction program at Theater of the Sea.

Photo Credit: K. Rivera

A green aracari at the Nashville Zoo is cued to hop across guests' arms during a public presentation.

Photo Credit: Nashville Zoo

A California sea lion is cued to wave at a small child at the Turtle Back Zoo's underwater interaction window.

Photo Credit: Turtle Back Zoo

This is only a short overview of all the different ways operant conditioning training is used in zoos to help keep animals healthy, active, and engaged. Some of the things zoo animals have learned to do in recent years are spectacular. If you can imagine a behavior that might be beneficial to managing exotic animals, there's probably a zoo out there that has trained it. The best way to learn more is to follow the social media of your local zoological facility, because they love to showcase innovative training and animal breakthroughs in posts for the public.